By: Nathan Ruibal

On the day that Brandon K., an extended-care resident, checked into Beit T’Shuvah, he sat outside for over two hours, talking to his ex-girlfriend who had dropped him off. He was unsure if this was the right place for him. “I was still fighting those demons,” he remembers.

Brandon was more desperate than he had ever been. From the time he was 16, after his mom left him on his own, he was always able to pull through and survive. “I asked myself, is this something that I can just deal with on my own?” He realized his situation was beyond his capabilities and that he needed to be open-minded and allow others to help him.

Brandon was raised by his great-grandmother, but his mother took him back when he was ten years old and moved him to Kansas. “I was a little bit rebellious because she had taken me from the situation I was already comfortable with.” His mother was a heavy drinker, which discouraged him from drinking himself: “I never did anything at that time, but it was always around in my neighborhood.”

Over time, Brandon got more involved in the street situation. “I was around gang bangers and people older than me. I still wasn’t engaging in it, but I was immersed in the environment.” At 16, Brandon’s mom told him she was moving to Oklahoma, and that he could come with her or not. He didn’t want to move again, leaving his friends behind “One day I came home from school and all my stuff was outside. She had left.” The next day he dropped out of school. “I had to work full-time and I had to figure out what I was going to do.”

Feeling abandoned, Brandon grew more comfortable with the people and the crime in the neighborhood. “That’s when I rally started to drink, and the first thing I started to drink was Bacardi 151 rum.” He also started selling drugs: “I got a hold of ecstasy and used that a lot. I also used to drink promethazine-codeine cough syrup. I was always heavily sedated.” He abused those drugs for many years, but was still able to function. He bought recording equipment and got into the music scene. “I started to do shows around town and gained some popularity in that city.” Brandon also started a clothing line company with an investment partner, but even all this creativity and ambition waesn’t enough. “I had hit a ceiling because there was nothing else for me to do.”

At age 17, Brandon was involved in a robbery of a bank inside a grocery store. “I got away with $100,000.” He used some of the money to pay some guys to get rid of the vehicle, but instead, they took the vehicle to the mall and spent the money they had been given. They got caught and they told the cops of Brandon’s involvement, and he got arrested. “I was in jail when my daughter was born.” He was adjudicated as an adult and had a felony on his record by the time he turned 18.

When he was 24, Brandon’s father invited him to move out to California and live with him in the San Bernardino area. He started school for music engineering in Hollywood, which forced him to get up every morning at 4:00 am. He soon entered a program called GRAMMY U, where they give students a sneak peek into the industry. One day he got an e-mail from GRAMMY U asking him if he could DJ the Grammy screening process. Even though he never DJed, he said yes. “I researched DJing for like a whole night and a half.”

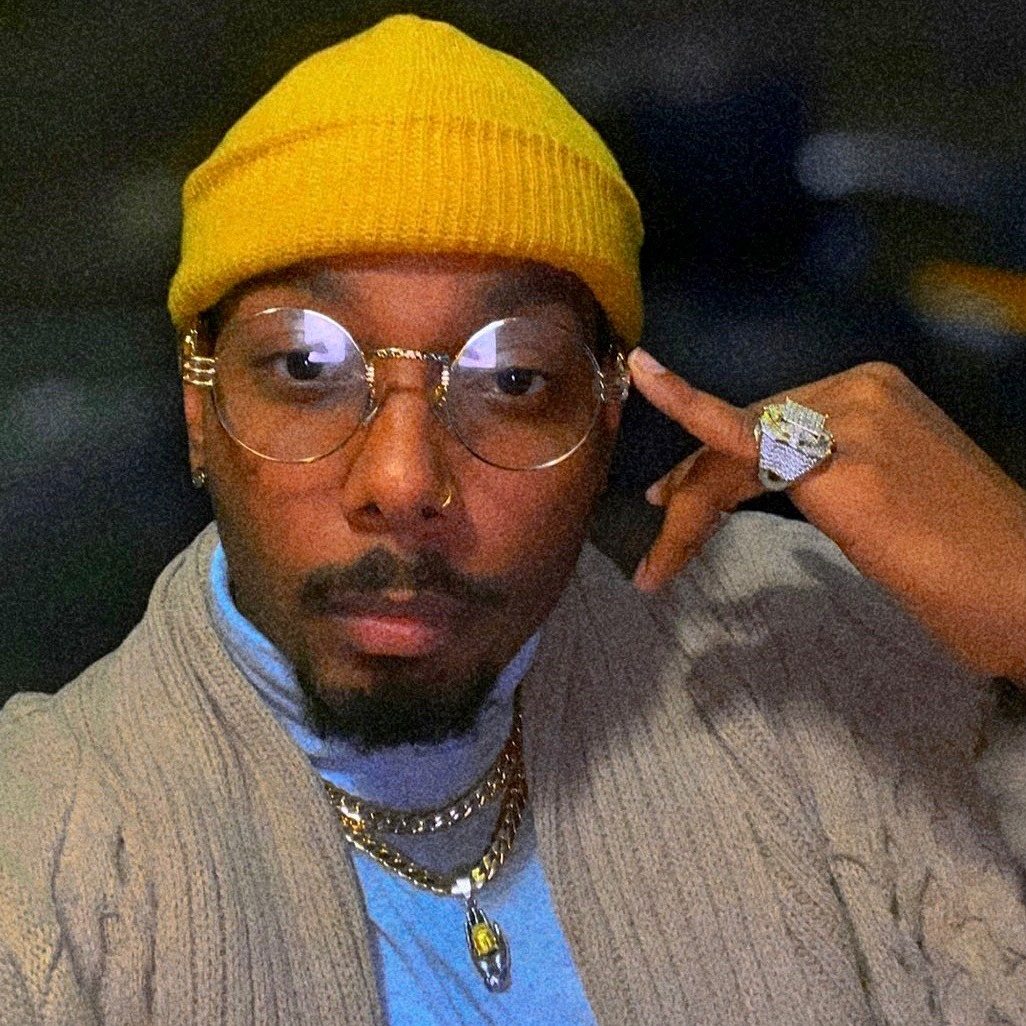

At the end of the four-day event, the head of R&B and Hip Hop introduced him to a prominent producer, who invited Brandon to come to his studio. He moved to Hollywood soon after and was in the studio every day. Brandon eventually became the producer’s chief engineer, which opened him up to many opportunities. “From that point, I was really in the industry.” Brandon went on to score some Netflix films. “I had all kinds of confidence,” he says. In 2019, he was nominated for a Grammy for his work on Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Suddenly the world changed when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Brandon’s drug abuse had been in the background for a while. “It was always around, especially in the music industry.” With the pandemic, gigs started to fall through and he eventually lost contracts with a lot of venues. He abused Adderall to the point where he had an episode of psychosis. His apartment caught on fire and he got charged with arson and went to jail for two months. “I didn’t want to ask for help from anybody, because I didn’t want to get blacklisted from the music industry.”

His then-girlfriend set up a GoFundMe page, which raised enough money for him to hire an attorney. Additionally, a non-profit heard his story and bonded him out of jail. The pending charges against him kept him depressed though. “I was looking at up to 18 years in prison.” Having the threat of a long sentence looming over him, plus the lack of work due to the pandemic pushed him to using again. “I went right back to Adderall and drinking.”

A friend of Brandon’s, with whom he did music, had a friend who went through Beit T’Shuvah. “He told me I needed to go to Beit T’Shuvah, and that they had a music studio.” Although hesitant at first, he came around to the idea of entering rehab. “Everything kind of hit me at one time. My professional life had fallen apart, my relationship had become super complicated, I missed my daughter’s birthday. I was in such a dark space. I was taking as many pills as I could, drinking as much as I could.”

Brandon felt like the universe was pushing him towards Beit T’Shuvah. “I’m the type of person to whom something drastic has to happen for me to accept it or go with it.” He saw Beit T’Shuvah as a place where he could explore his spirituality. “That was one thing I didn’t have the answers to. When it came down to spirituality and community, that’s where I lacked because I was always like a lone wolf.”

During his time here, Brandon has become an integral part of the music department, through his work therapy internship. “I work with residents, helping them get their ideas out. I mix the Shabbat services.” He’s proud to be able to merge his professional know-how and urge to be of service to the community. He’s also teaching people how to use the recording programs, how to vocal produce, helping people get in touch with their inside artists. “I try to help develop and mold, just get people’s vision out. It’s being of service.”